Embedding Access in the Arts

Article 19 discusses the intersection of inclusivity with arts and culture

Accessibility, advocacy, and the intersection of inclusivity with arts and culture—we explore these topics and more with Tamman’s new Senior Director of Education, Katie Samson. Drawing on her lived and professional experiences, Katie shares insights on projects like Carolyn Lazard’s Long Take and emphasizes the importance of embedding access into creative practices. Ultimately, uncovering how collective access can drive meaningful change in the arts and beyond.

Meet our guest:

Katie Samson is an educator, disability self-advocate, and storyteller who works in the intersection of accessibility and inclusion online and in public spaces. With a decade of experience in arts and culture, she is now the Senior Director of Education at Tamman, Inc. & Chax Training and Consulting.

Listen to more Article 19 Podcast Episodes

Full Transcript

Access the PDF Transcript

Kristen Witucki:

Hello Everyone and welcome to Article 19. I’m Kristen Witucki, content creator and accessibility specialist at Tamman. And, I’m the host for our current conversation. Today, I’m bringing you a really exciting episode because Katie Samson, Senior Director of Education at Tamman is joining us today as a guest, but, tomorrow, she may be a host or a co-host. Or, helping me with the writing and editing. So, I’m really excited to turn Article 19 into this combination of disability-lived experiences, professional experiences, and everything else the two of us can come up with. Article 19 is a call for others to join us in a larger conversation around digital accessibility, the ADA, and access to information. At Tamman, we are working really hard to build the inclusive web every day. But, to join us, we need everyone working together, and learning together. Thank you so much for listening to Article 19.

Produced Introduction with music bed:

Expression is one of the most powerful tools we have. A voice, a pen, a keyboard. The real change which must give to people throughout the world their human rights must come about in the hearts of people. We must want our fellow human beings to have rights and freedoms which give them dignity. Article 19 is the voice in the room.

Kristen Witucki:

So without further ado, I’d like to introduce Katie Samson, who is our Director of Education at Tamman and who most recently was Director of Education at ArtReach, but has a wide variety of life experiences and professional experiences around disability, education, the arts and culture. Katie, welcome to the podcast.

Katie Samson:

Thanks, Kristen. It’s great to be here. And I’m really excited to be kicking off a beautiful relationship and collaboration.

Kristen Witucki:

Me too. So, this is a bit of a conventional beginning. But could you tell me a bit about your background and how you came to join us at Tamman?

Katie Samson:

It’s a great starting-off question. I came into disability inclusion and accessibility work in arts and cultural spaces from a background as a museum educator. And I went to graduate school to study art history. I thought I was going to hang out in museums for the rest of my life and that would be it. And as I transitioned into learning about underrepresented communities and having some really incredible experiences with working at an alternative high school inside a museum, working with veterans coming back from Iraq and Afghanistan, inside a rare book library. I started to identify some barriers, and, as well as some gaps within the learning and the conversation and the practice of being inclusive and being accessible. And this opportunity came about in 2018 to pool my understanding of interpreting in museum spaces and arts and cultural spaces, as well as I had been teaching disability studies as a side hustle. Although I won’t necessarily say it was the most lucrative side hustle, it was very rewarding. And I really enjoyed my time at West Chester University outside Philadelphia. But the thing that I got really excited about is I could really merge my passions about advocacy, accessibility, and inclusion into public spaces that were focused in arts and culture. And I tend to think that in art spaces, they tend to be a bit more progressive, a bit more radical and take more chances and hopefully have the funding to do so. And I’ve just been very excited to get in the weeds with a lot of different arts and cultural partners in the Philadelphia region where a lot of my work is focused. And then during the pandemic, really branching out to national and international organizations to provide expertise, feedback, programming ideas, and also coming from a place of lived experience. I am a quadriplegic. I’ve been a wheelchair user for 24 years. And I’m also hard of hearing. I have single-sided deafness and vestibular damage, which can affect sometimes day-to-day depending on barometric pressure or dizziness or things like that. And I think often times when we talk about accessibility and we talk about inclusion, honoring that lived experience is something I think is incredibly valuable and it was one of the big reasons why I decided to come over and work at Tamman because I saw it happening with my own eyes. I could listen to it on the podcast and I could really feel it in the space.

Kristen Witucki:

Also, I’ve talked to many Tamman employees now and I forget who said it, but one of them was saying that they had been there for five or six years and still felt that way, which is just kind of incredible. When we think about the arts and culture space, what are some developments for people with disabilities that you’ve found really exciting over the past couple years?

Katie Samson:

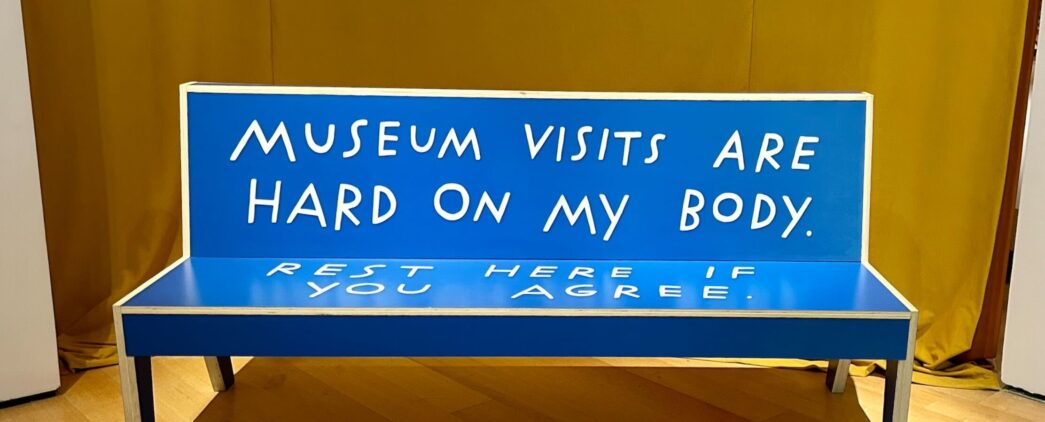

There’s a lot I could name, and I’m actually going to give a couple of examples because most recently I think had a tremendous impact on our community here in Philadelphia, and I could see them and experience them firsthand. One of which was a collaboration that was done at the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania with a artist by the name of Carolyn Lazard. That’s L-A-Z-A-R-D. And she works across a lot of mediums considering aesthetics and a lot of conversations around dependency, care, and access. She has a disability herself. And she works really as a collective, both with the organization that is providing the space to facilitate the work that she’s doing, as well as working with a lot of different disabled artists. And they put on a piece called Long Take. And it was a solo exhibition that was actually a dance, but it wasn’t a dance that you could see live in person. It was a choreographed performance that was filmed and videotaped. And when you came into the space, all you actually experienced was the sounds and the captioning on various different channels throughout a large curated space. And what I thought was so interesting is one of the channels of sound was the movement of the dancer, sort of sweating it out and a little bit of grunting, a little bit of moaning, things like that. So there was that layer. And then there was maybe the layer of talking through the choreographed phrases of a dance. So some more of that dance language. It was really remarkable because your experience is as a listener, and then you’re also reading the captioning. What was so tremendous about Carolyn’s work is she worked with the organization, not only to provide comfortable seating for people with disabilities that needed to sit for a long period of time, but all of the accessibility features for people who were blind and low vision, for people who were deaf or hard of hearing, they were all embedded into the piece. And so Carolyn is one of many artists that is now shifting in this way of providing accessibility from an aesthetic perspective, from a place of beauty, from a place of recognition, that it can be subjective rather than just sort of here is your large print or Braille description. Here is the verbal description in a very objective and straightforward way. And here is a captioning and ASL interpretation of the artist speaking about the project. And that’s kind of all you get. And maybe a little bit of physical access there. So it was tremendously inclusive and also immersive. And it also wasn’t for everybody. You know, there were people who were neurodiverse that was like sensory overload, like, no, thank you. There were people who are low vision that thought the space was too dark. So, you know, when we try really hard to do inclusive, artistic, pieces like this, you can’t universally design for everybody, but you can try. And I think what was so tremendous about this piece is there was an effort not only to try, but all of the thought went in from the very beginning conversations and started to ask questions about access needs with the artist as they were building into the space, which I think is the best way to go. And it’s the best way to build that sense of trust with the people that you’re hoping come and see the art and experience the art. And then also just from the stake of hiring disabled artists to feature their work and exhibiting their work in spaces. And for that young person of color, that’s coming into an artistic space and seeing that there is a black disabled woman that identifies as being disabled and recognizing the power and the skill set that that can bring into art circles, I think, is where I am most excited about. And that’s the art that I want to celebrate.

Kristen Witucki:

That’s such a cool experience to imagine, like just that all of the things that have traditionally been hidden, like the technical aspects of the art sort of become part of the art and that idea that the participants are also part of the art. It just kind of shows that forethought and the way it was built from the beginning with the audience of diverse people in mind. So that’s really cool. Any other exciting developments you want to talk about?

Katie Samson:

Yeah, there is one that it was a project that came out of the Temple Institute of Disability. It’s called File/Life. We remember stories of Pennhurst and for many of you that are out there in the world that don’t know or don’t really have that much knowledge about institutions like Pennhurst, these were state-run facilities for people primarily with intellectual disabilities. And for many instances like the one at Pennhurst, they had been closed down due to human rights violations. And what the project involved, a group of community archivists that were brought in to look at the medical records of the people that lived within Pennhurst to try to bring more understanding, more awareness, and more humanity into what was an extremely complicated, very sad, and very difficult life for many of these people. And what I found was so tremendous about this project and should be sort of the regular mode of thought is a number of the community archivists that were involved in this project, not only were residents of Pennhurst and lived there and were invited into the archives but other individuals within the community who have intellectual disabilities themselves. And it was a recognition that people with lived experience with intellectual disabilities have a very strong message, voice, community of concern to bring into archival spaces. And it brought up a lot of questions. It brought up a lot of conversations, but it also sort of like we let archivists into collections because they’re experts in handling material and they know how to catalog things really well. But who are we also leaving out of that opportunity to engage with historical records, historical materials, and what stories are yet to be told from these communities? And I’ll never forget, I had a conversation with one of the arch gvsivists, a young man by the name of Jonathan Atencia. His subject in the file that he was looking at as a community archivist had an intellectual disability and he had escaped from Pennhurst like over six times. And what we know about a lot of people with intellectual and cognitive disabilities is often times the sort of standard way of learning is different. And for Jonathan in particular, as someone with an intellectual disability that’s navigating in higher education and trying to get a degree, he wanted to feel what that was like. So he went to Pennhurst and he put himself within the actual building and he sort of reenacted, embodied that experience, like the proprioceptive experience of trying to escape Pennhurst. And to him, to be able to articulate both as an archivist to say I needed to have that embodiment experience to understand it and to be able to share that out as an archivist. I was really blown away by that. And we can all learn from that. Right? That’s just like, sometimes you have to feel the space to learn about the space. Sometimes you have to move in the space to learn about the space. And sometimes you have to invite people from all walks of life to come in to see and be exposed to this. And I couldn’t be prouder about that being a kind of at the forefront of the conversations we’re having in public history. And that was really cool. And the exhibit that came of this project was one of the most accessible museum installations I’d ever participated in. So I encourage people to check that out. That was like Temple Disability Institute and the Office of Media Arts and Culture. And the show is called File Life.

Kristen Witucki:

What are the challenges that organizations are having in making art truly accessible and inclusive for as many people as possible?

Katie Samson:

There are many challenges that organizations are having. Not gonna lie. Many of them revolve around funding for accessible services. There are many service providers out there doing incredible work, whether it’s CART captioners for people who are hard of hearing, audio describers for the blind and low vision community, ASL interpreters, you name it. And that is a labor and we should pay for that labor. I will also say that a big challenge is there is someone within the organization that is incredibly passionate, attends conferences, goes to webinars, embeds themselves within this work. And for whatever reason, they move on. Bravo for them. They go to another organization, they go to another place. And what my friend and former colleague Maria Broswell said is she calls them the lone bellow. And the lone bellow is this shouting voice within the organization saying, we need to do more accessibility or that’s not accessible. This isn’t accessible. We need to do better. When that lone bellow leaves, there is not a lot of institutional knowledge and memory to hold the organization accountable. And what I find some of the biggest challenges are is updating policies, procedures, and practices that create a culture that not only centers the disability experience, but really centers the human experience. Because we all have needs, right? We all have shifting needs. COVID taught us that and many of us pivoted and balanced out our lives as best we could during that practice, you know, whether it was masking or working indoors and all these things. So we understand how to motivate ourselves towards that change. And yet, as far as I know, people have been blind for many, many years and people have been disabled for many, many years. That’s not going to change. And we have civil rights laws that, help us get there. What I find is problematic about the ADA is it doesn’t have a lot of teeth to it, especially for nonprofits. And, what we need is community members almost to be a part of those decision-making processes, to not make these policies, practices, and procedures in isolation and without the voice of your community that you’re wishing to serve. And I think a lot of these challenges have been exacerbated as we’ve sort of, oh, we’re back. We’re going to open up our doors and, you know, come on in and we want to serve you as best we can. And we’re also starting from a place of deficit where a lot of arts organizations lost funding, especially performing arts, theaters, things like that. And I think the way that we get there, there has to be a process, a ramping up. So a lot of organizations don’t feel like they have to do it all in a year that there are low hanging fruit to pluck from to just get started on some of the basics and then go from there. Hop on the train. It is still moving, but we can build some ramps that get you on that train a little bit easier and we can provide some guidelines to get you there. I think Tamman is a lot of that conversation and is really providing that opportunity to for whether it’s a company, an organization, one person, that one lone bellow to say, hey, in the workroom or at the water cooler to say, hey, I’ve been listening to this podcast and I think we could probably do better on workforce accommodations and things. We’re getting there.

Kristen Witucki:

What are some examples of those low-hanging fruit or just some small ways that orgs can get started?

Katie Samson:

I talk a lot about in planning for understanding inclusivity and what that means is a principle that really goes back to one of the principles of disability justice that was formulated by a performing arts troupe out of the Pacific Northwest called Sins Invalid. And they came up with a very intentional and thoughtful way to think about disability justice that involves, not just people with disabilities, but Indigenous folks, LGBTQIA folks, people of color, immigrants to consider this idea of collective access. And we’ve been talking about it even in just my first three weeks at Tamman and what collective access could mean. A lot of that is just kind of normalizing what we think about as accessible needs, accessible accommodations, and being open to speaking about them in a way that doesn’t objectify a person or doesn’t make them feel pity, but the same way that you might have to excuse yourself working from home because you’ve got some pipes that burst in your bathroom and the plumber’s over and you have to mute and keep your video off for a meeting. You know you might share some of your access needs or accommodations right from the top of a meeting. So I think just that idea of fluidity, I think this concept of bringing your whole self to whatever experience you might have, you know, in the workplace, and that’s not for everybody. There’s plenty of people out there with disabilities that don’t feel comfortable or confident in sharing that identity, because we’ve seen what work discrimination looks like, and it doesn’t paint a pretty picture of our past. That’s not a reason to not think about it in the future.

Kristen Witucki:

What are individuals in the disability arts and culture spaces doing to address some of these challenges of people not being fully educated about access and inclusion? Or, I mean, I guess the really tough one is the lack of funding, but what are people doing to alleviate those barriers?

Katie Samson:

Yeah, I think my former colleague at ArtReach, the managing director, Dani Rose, she has this great quote that she says, “turn your complainers into consultants.” And I love that idea. I back that up to say, like, “if we build it, we will come.” You know, like the field of dreams approach, but thinking about it from the disabilities perspective. If you want to build a more inclusive environment, a more inclusive organization, bring in the folks that you need to collaborate with who know the best and have the best knowledge of this. And those are the people that live through it every day. And the way that organizations can really tap into this incredible resource that’s just outside their doors, I think is a relatively new concept. And it brings a lot of humility into spaces that haven’t always felt like they have a lot of humility understanding that as an organization, as a museum, as a big temple on the mountaintop, that everybody within those walls has learning to do and don’t understand everything. And I think most importantly are going to make mistakes and frankly have to make mistakes to learn better and to do better. I think just trying and failing is a big part of like, you know, sort of restorative practices. And one of the things that I see is this really trepidation into just trying something, engaging with the public, piloting one small thing and then getting feedback and then keep going and trying it again and working with partners and really understanding who’s in your neighborhood. Like, I love that. Who are the people in your neighborhood song?

Kristen Witucki:

Yeah.

Katie Samson:

That’s really big, really kind of mapping out your community and to understand, are you meeting the needs of your neighbors? And that’s the low hanging fruit. Just take a stroll around your neighborhood and be like, that organization just popped up, that library, that service organization, this place. I mean, sometimes the best people to know and to learn from are your local post person that’s going door to door, that can really tell you what’s new and what’s different about your neighborhood and people that they might want to touch base with. And Yeah, so I think walk your block or stroll around your block and figure out who that community is and who you’re not serving and ask those questions internally. Why? Why not? And what is the barriers to that?

Kristen Witucki:

I love that. And it’s so cool that you’ve joined Tamman and that you can kind of increase that presence in the education and research and really engaging with the community that we are already working with. So I am thrilled that you can help us to do that even better. Well Katie, I don’t know how to end this. I mean, It’s been so great chatting with you and getting to know you during your short time at Tamman.

Katie Samson:

Thank you so much. It’s been so fun and you’re really good at this by the way..

Kristen Witucki:

So are you. Why don’t we just try it. You can help me host the outro.

Katie Samson:

Okay. So outro. Like I just say… Thank you Kristen for this opportunity. It was a pleasure. Thank you Markus Goldman Executive Producer. And, we all gotta thank our production support from Steven Stufflebeam. Is that it? How’d I do?

Kristen Witucki:

You did great. And everyone, if you like what you heard today, and want to explore more about digital accessibility, technology, our company culture, or really anything, because we are always up for chatting about anything. Just schedule a time to meet with us. You can find the whole Tamman team at Tamman Inc. Dot Com. That’s T-A-M-M-A-N-I-N-C.com. Don’t forget to sign up for our newsletter, follow us on social media, and please let your friends and family know about Article 19 on your favorite platform. Until next time, it’s been really wonderful and real. Thank you so much for listening and being a part of article 19. Take care.

Show Notes

- Carolyn Lazard: Long Take: Her debut solo exhibition in Philadelphia, Long Take continues Lazard’s ongoing experimentation with methodologies of access

- File/Life: An exhibit remembering the stories of Pennhurst

- Art Reach: A Philadelphia-based organization that creates, advocates for, and expands accessible opportunities in the arts so the full spectrum of society is served